Chile's Ancient Mummies

More than 7,000 years ago,

hunter-gatherers used elaborate techniques to preserve their dead

by Marvin Allison

(All of the pictures have been taken

from National Geographic Magazine, March 1995, pages 69-81; the text is

taken Natural History Magazine, October 1985.)

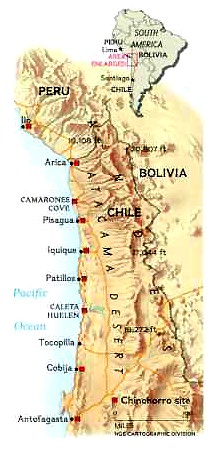

Arica, Chile's northernmost port, thrives in

defiance of the arid lands that surround it. The lifeline for the city and

its more than 100,000 inhabitants is the San Juan River, a tiny line of

fresh, sweet water that threads its way out of the Andean foothills and

across some seventy-five miles of the world's driest descent to the

Pacific Ocean.

A tall promontory, El Morro, looms above the

southern edge of the city. Late in 1983, a ditch- digging machine was

cutting a trench for a new waterline on El Morro's lower slopes when its

blades began to churn up the legs and broken bodies of men, women, and

children. The pipeline project had intruded into a pre-Columbian

graveyard. In time, teams of archeologists and students uncovered

the remains of 96 individuals, a most valuable addition to the growing

collection of more than 1,500 mummies at the university's Museum of

Archeology.

With ever improving techniques of analysis and

dating, these mummies, along with smaller collections at other

institutions in Chile, are providing unprecedented insights into the early

history of human disease, nutrition, and culture, including a practice of

mummification more complex than the Egyptian process, even though it is

two to three thousand years older. Our oldest specimens are, by far, the

oldest-known mummies in the world.

Mummification can occur naturally, with the right

environmental conditions, or artificially, when humans take steps to

preserve a corpse. The conditions in northern Chile are excellent for

natural mummification. Because the cold Humboldt current upwells off the

coast, the warmer air collects little moisture from the Pacific Ocean.

Thus, from the coast to the foothills of the Andes, it almost never rains.

Years pass without rain, and in those rare years when some rain does fall,

it is not heavy enough to penetrate a foot or more of soil. The absence of

moisture, not just for years or centuries but for millennia is the main

reason for this unsurpassed collection of mummies.

Bodies discovered in an unmarked colonial

graveyard about ten miles east of Arica at the Church of San Miguel

illustrate the importance of aridity. The small church is next to an

ancient Indian burial site where people have been interred mostly  without

anificial mummificationfor nearly 3,000 years. The corpses of the ancient

Indians are dehydrated, but their bones are still firmly attached, their

skin and hair still present. In contrast, the remains of the colonials,

buried in front of the church, were mostly nothing but bones. We were

puzzled by this difference until we discovered that attendants always

sprinkled irrigation water around the church to keep down the dust.

Moisture, penetrating the soil and the graves, had caused the corpses to

deteriorate. without

anificial mummificationfor nearly 3,000 years. The corpses of the ancient

Indians are dehydrated, but their bones are still firmly attached, their

skin and hair still present. In contrast, the remains of the colonials,

buried in front of the church, were mostly nothing but bones. We were

puzzled by this difference until we discovered that attendants always

sprinkled irrigation water around the church to keep down the dust.

Moisture, penetrating the soil and the graves, had caused the corpses to

deteriorate.

The burial practices of the ancient Indians

probably helped preserve the corpses. Bodies were usually placed in

shallow holes in seated, huddled positions, and then covered with cloth

and reed mats. Under the strong sun, these grave sites were, in effect,

solar ovens in which the corpse quickly dried out. In time, windblown sand

drifted over the grave, further preserving the cadaver. And finally, the

large amounts of salts, including nitrates, in the soil acted as natural

preservatives.

In 1919, Max Uhle, the first archeologist to

study these mummies, assumed that the natural mummies he found were the

oldest and most primitive, while the elaborately prepared anificial

mummies were more recent. Without the benefits of modern dating methods,

he estimated the primitive mummies were about 2,000 years old. Uhle named

these people the Chinchorro, or gill netters, recognizing their maritime

location and fishing practices. We still use Uhle's name for these early

Americans, as well as his classifications for mummy types, but carbon 14

dating has revealed two surprises.

First, the oldest Chinchorro are four times older

than Uhle's estimate. Our oldest mummy has been dated at 7,810 years B.P.

(before the present), plus or minus 180 years. Hans Niemeyer, who has

excavated Chinchorro sites in the Camarones Valley sixty-five miles south

of Arica, has obtained carbon dates of 7,420 B.P. and 7,000 B.P. With a

series of carbon 14 dates, using material from the mummies, we now

estimate the Chinchorro culture extended roughly from 7,800 to 3,800 B.P.

The Chinchorro were probably closely related to another preceramic culture

of the area, the Quiani (3,400 to 3,200 B.P.), and to the Faldas de Morro,

a group with the first ceramics and metals in the area (2,800 B.P.). In

short, in one small area we have found human and cultural remains that

span a 5,000-year period. And some preliminary genetic and anthropometric

studies indicate that all these people were closely related.

The second surprise from the dating was that the

7,800-year-old body, a man of about thirty- five years, was not a natural

mummy but was instead an example of one of the most complex forms of

mummification. This discovery raises all sorts of questions: Are there

older mummies yet to be found? Where did the idea and the skills of

mummification come from? How long have humans with complex cultures been

in the Americas? These questions, and others, lead to interesting

speculations; but since I am a paleopathologist, I spend my time studying

the bodies and the artifacts found with them. The data they contain are

fascinating enough for me.

The ninety-six bodies from El Morro, as indicated

by carbon 14 dates, were interred over a period of more than 3,000 years.

They represent all types of mummification, from simple air drying to the

elaborate classic style. While there are many variations, all thirty-five

classic mummies

show the Chinchorro had techniques and a knowledge of anatomy that

contradict any notion that they were primitive, even though they had

neither metal nor ceramics.

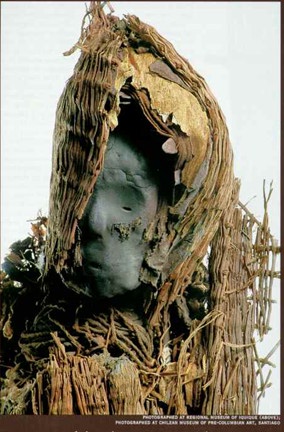

The first step for a classic mummification

involved a careful incision in the cadaver and the removal of the internal

organs, which deteriorate quickly. The skin and hair were cut away from

the corpse, and major muscles were removed. The brain was removed through

an opening cut in the skull or by hooking it out through the foremen

magnum (the opening at the base of the skull). All this was done without

metal knives. The embalmers used sharpened stones and shells and the

sharpened beaks of pelicans. We have found a number of these beaks in

grave sites. After 5,000 years they are still sharp, strong, and effective

tools.

The body was quickly dried by filling it with hot

coals and ashes. The skin and hair probably were soaked in salt water.

Then the mummy makers - who were most likely specialists in the tribe -

took a number of steps to make the corpse rigid. They rubbed the elbow and

knee joints with abrasive stones until the bones were flat and then bound

them together with fiber ropes. Another fiber rope ran down the arms and

across the chest at the level of the collarbones to prevent the chest

cavity from flopping open. They drove a sharpened stick under the flesh

along the spinal column and tied the vertebrae to this stake. Two other

sticks were inserted from each ankle to the skull.

When the body was rigid and dry, the mummy makers

wrapped reed matting along the legs and arms, and across the shoulders.

They filled the body cavity with wool, feathers, grass, shells, and earth.

After binding the halves of the skull together with fiber cord, they

wedged it on the ends of wooden poles at the neck and over the rope- bound

vertebrae. To give the mummy a lifelike shape, the Indians molded clay

over the limbs. Since the kneecaps had been discarded, the skin at the

knees was cut and sewed tight.

The mummy makers sculpted a face mask of clay,

with holes for the eyes and mouth. They tied the corpse's hair in bunches

and bound it to the mask with rope. They painted the mummy black during

some periods, red during others.

There were many minor variations from this

procedure. Children were often simply eviscerated through an incision in

the abdomen and filled with ashes and hot coals. Poles were tied to the

legs or slipped under the skin. In other cases, skin on children was cut

in strips and wrapped around their bodies like a bandage. With some

mummies, the skins of other animals - often pelicans or sea lions - were

used to cover the bodies. In all cases, the idea was to make the body

rigid and rebuild it to lifelike dimensions.

When the mummy was finished, it was not buried. Apparently as some form

of ancestor worship, mummies were propped up in groups and continued to

inhabit the community; perhaps in a spiritual sense they helped to bring

good hunting and fishing to their descendants. In return, the living kept

the dead in good condition, as indicated by the repairs on many mummies.

Eventually, possibly when certain influential people died, the older

mummies were buried in small groups. Since many burial groups contained

adults and children, perhaps

the deceased were interred as a family.

We also found many plant and animal remains at

the grave sites. These materials, along with the mummies and even the

campsite dirt stuffed into the mummies, have provided us with many clues

about the daily lives of the Chinchorro. The early Indians were hunters

and gatherers, living mainly on products from the sea. They used

sophisticated gill

nets to catch fish off the beaches (a method

still used by some Indians in the area today). They hunted sea birds and

marine mammals, particularly the sea lion, which they speared with a barbed

harpoon.

The Chinchorro did not practice agriculture, with

the possible exception of growing reeds for mats and fiber. They used the

products of their environment pelican beaks and feathers, seashells, sea

lion hides, and even whalebone for practically all their needs. We have

found some use of feathers and llama wool, which would indicate the

coastal Chinchorro traded with the inhabitants of the Andean highlands.

The Chinchorro men suffered from one of the

earliest known occupational diseases; one-quarter of them had a bony

growth in the ear canal - probably the result of  multiple

ear infections - that would have led to deafness. Such growths are common

in people who dive persistently for shellfish.

Since none of the women had this lesion, they apparently did not go shell

fishing. The women did, however, have "squatting facets" at the

ankle-shinbone joint. These lesions occur when people work in a squatting

position - in this case, probably opening shellfish. Nearly half the women

had an arthritic degeneration of the neck vertebrae, probably from

carrying heavy loads. multiple

ear infections - that would have led to deafness. Such growths are common

in people who dive persistently for shellfish.

Since none of the women had this lesion, they apparently did not go shell

fishing. The women did, however, have "squatting facets" at the

ankle-shinbone joint. These lesions occur when people work in a squatting

position - in this case, probably opening shellfish. Nearly half the women

had an arthritic degeneration of the neck vertebrae, probably from

carrying heavy loads.

This division of labor, as well as the complex

processes of mummification, means that individuals among the Chinchorro

had specialized jobs and clear roles according to sex. This is unusual for

such an early, small, and isolated group of humans. In later cultures, the

practice of mummification degenerated, and judging from the hunting and

fishing gear webbing buried with both women and men, the roles of the

sexes merged.

Because

of my interest in pathology, I usually focus on diseases and causes of

death, but I do not want to give the impression that the Chinchorro were

sickly. They appeared to eat a relatively

high-protein diet and to lead active, healthy lives. Because

of my interest in pathology, I usually focus on diseases and causes of

death, but I do not want to give the impression that the Chinchorro were

sickly. They appeared to eat a relatively

high-protein diet and to lead active, healthy lives.

As one of my younger associates noted, holding up

a skull of a middle-aged man, the mummy's teeth were in much better

condition than his own. In later cultures, when irrigation agriculture

came to the valley, Indians ate more carbohydrates and less protein. And

the teeth of these later Indians have many more cavities. Unlike the

Chinchorro, their successors knew the agony of a toothache.

For perhaps 15,000 years, if not longer, the

western coast of South America for hundreds of miles north and south of

Arica has been dominated by inhospitable desert. Only a few isolated

groups of Indians, clustered around rare sources of fresh water, managed

to eke out a living. In their narrow niche, these Indians lived

differently and apart from the major groups and Indian civilizations of

the Andean highlands and the continental interior. Some preliminary

genetic surveys indicate these Indians were the direct descendants of

earlier tribes that lived in the region for many thousands of years. Such

continuity is without precedent anywhere else in the world.

And the arid conditions that so shaped their

lives also preserved them in death. As our techniques of analysis improve,

we will learn more about the daily lives and conditions of these obscure

Indians than we know about any other group in prehistory. After nearly

8,000 years of silence, the Chinchorro are beginning to tell their story,

and we have much to learn about them - and ourselves.

www.mc.maricopa.edu/.

../legacy/chincho/ |